I’m so pleased to welcome Violet Grey (@v_greyauthor) back as a guest blogger today. In previous posts she’s done sterling work shattering the idea that women can’t be submissive feminists, tackling the headlines about millennials not having enough sex, and sharing extremely hot erotica about being humiliated and used. Today, she’s here to teach us about a cinematic trope that really pisses her off. As a bisexual woman, she is sick of seeing LGBTQ+ characters routinely killed off, so she is here with a message for screenwriters: don’t bury your gays.

Don’t bury your gays

One night a few years ago I was flipping through TV channels. I decided to settle on Alien: Covenant. I knew it wouldn’t be anywhere near as good as the first two films of the franchise, but it’s in the Alien series, so I decided to watch. Ten minutes in I changed the channel. Why?

Well, when the aliens start to make themselves known to the crew, a small group of explorers finding a planet to settle and populate, an alien jumps out of the reeds on the planet. It leaps out, past the other characters, to a male settler’s husband, killing him instantly. They were the only gay couple in the film.

I was angry, because for what felt like the millionth time I, a bisexual woman, saw yet another LGBTQ character die unnecessarily on screen. Surely the sexuality of the character shouldn’t matter, you say? I agree! But unfortunately people who are judgemental, even hateful, of someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity make it a problem, and so LGBTQ characters in film and TV are disproportionately censored, portrayed negatively and/or killed off.

There are many widely known tropes used in literature, TV and film. The jock and nerd secret romance, the wallflower turned ‘hot’ after a ‘makeover’, the tortured artist, the list is endless. But one that stands out, particularly if you’re LGBTQ, is a trope known as ‘Bury Your Gays’.

Bury your gays

‘Bury your gays’ is a trope where queer characters, due to the circumstances of the plot, cannot live as their true self and die by the end of the story. While this can happen to heterosexual characters, these plot points happen disproportionately more often to LGBTQ characters than their straight counterparts. A recent example is the on screen relationship (often speculated to be LGBTQ, then later confirmed in the series finale) between Dean Winchester and Castiel in Supernatural.

Some circumstances for queer characters are completely in context and accurately portrayed i.e. the secrecy of Ennis and Jack’s relationship in Brokeback Mountain, the tragic true story of murdered transgender man Brandon Teena in the critically acclaimed film Boys Don’t Cry, and Garrard Conley’s memoir and film of the same name – Boy Erased – a first-hand account of surviving conversion therapy. But in stories where this isn’t the context, queer characters repeatedly draw the short straw. Why?

Queer coding

‘Queer coding’ means the character portraying traits often associated with LGBTQ people, but not explicitly stating whether or not they are. This can be linked to ‘queer-baiting’: speculating a possible LGBTQ character to draw in an audience, but never fully delivering, so as not to isolate or alienate other audience demographics, i.e. religious conservatives, essentially ‘baiting’ the audience. It’s essentially the ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ of cinema, primarily brought about by the Motion Picture Production Code in Hollywood’s Golden Age.

The Hays Code: Hollywood’s ‘answer’ to ‘immorality’

The Motion Picture Production Code, also known as The Hays Code, was a list of guidelines and regulations brought into American cinema with the aim of ‘rehabilitating’ American films – regulating what could and couldn’t be shown in cinema after religious leaders and conservatives objected to what was being shown in cinema.

Written by Martin Quigley, a conservative journalist, and Jesuit priest Father Daniel A. Lord, the code was brought to Hays in 1930, but not fully enforced until 1934. The code strictly enforced a stringent ethos of ‘morality’ which forbade the depiction of homosexuality (or ‘sexual perversion’ as the code referred to it – facepalm) taking the Lord’s name in vain (no ‘Oh God’s or ‘Jesus Christ!’ here), gore and interracial relationships (the code was also incredibly racist).

While the Hays Code ceased enforcement in 1968, it has still greatly affected how queer people are seen in society, many of the tropes it birthed still existing today. While the Hays Code is not solely responsible for anti-LGBTQ sentiment, it certainly has a lot to answer for.

The killing off the husband in Alien: Covenant example is one of many, countless even. Time and time again, we see queer characters (or suspected) depicted as villainous or a tragedy case, before meeting an untimely, usually horrific demise. If we’re not causing trouble, someone’s causing trouble for us.

If we’re not some of the first people to die in films, it’s a drawn out, agonising process of conversion therapy and other kinds of horrendous torture. If we’re not the (might I say utterly fabulous) villains ruining everyone else, we’re heavily stereotyped, adding to further negative reinforcement of queer people to viewers. In my case as a bisexual woman, seeing the routine fetishisation of bisexual women as a threesome-having, sleep-with-anyone-we-see sexual commodity for a straight audience, and the shaming of bisexual men as ‘gay men just biding their time.’

To put it politely: it fucking sucks, and we’re tired of it.

Preserve your gays

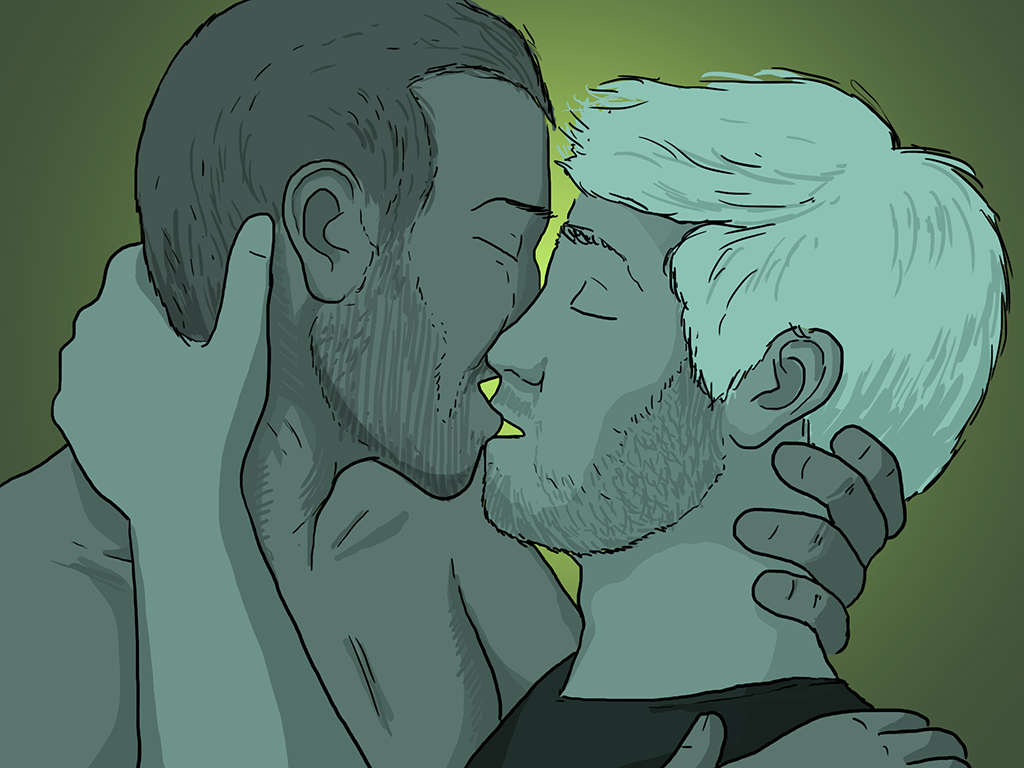

In growing retaliation to the censorship of queer characters or their routine untimely demises, cinema has birthed a new trope: ‘preserve your gays’, where writers will actively avoid unnecessary hardship or death of LGBTQ characters, instead favouring much-needed, more accurate representation of queer people on screen.

LGBTQ stories are important and need to be shown: the good, the bad and the ugly done to us at the hands of others. But after so much bad and ugly, it’s refreshing and joy-inducing to finally start to see some good. It might take a while to fully change, but I’m happy to see some starting to happen, from more accurate depictions of LGBTQ people to actually to important discussions around equal rights.

It’s about time we listen to our gays, rather than burying them.

2 Comments

💕💕💕

Let’s continue to support and demand meaningful representation that respects the lives and stories of queer individuals. #DontBuryYourGays